The everyday items that have been handed down at the Former Ouchi Residence are things like patchwork quilts made from old cloth, handmade bamboo chopsticks, and home-cooked food that uses every part of local produce. Seen from contemporary eyes, everything is sustainable and a forerunner of the circular economy.

We interviewed Ms. Maki Tanaka, of the Preservation Society of the Former Ouchi Residence, about how the preservation movement was begun and her hopes behind the dishes that she and her colleagues have made.

At first, so much time had passed since this house had become vacant that it was about to start collapsing. I then began working on preserving it, because as a resident of this town, I could not stand by and just watch such a historic home fall apart.

I had actually tried to start preservation efforts about ten years earlier, but it hadn’t worked out because I hadn’t been able to receive much support from the people around me. Then the house started leaking on a full scale and wasn’t going to stay standing after another winter, so I tried once again. This time, I called for cooperation nationwide, starting a signature drive and what was called a “single tile campaign” for 2,000-yen donations, each of which would be used to buy one roof tile.

Chozo Ouchi was the director of the Tung Wen College in Shanghai (in the 1930s). This college was established to bring Asia together in peace and put an end to war. War broke out soon afterwards, but Ouchi was a foremost figure in the anti-war effort. The Former Ouchi Residence is the birthplace of such an individual who held the kind of conviction that is most needed today.

Back in its heyday, the Former Ouchi Residence hosted many guests from the Korean peninsula and China. It had so much history and had been so cosmopolitan for such a provincial place that I felt it was very significant for this region to preserve this house.

When I was a child, the then head of the family and my father were good friends. However, it was just after the Pacific War had ended and they had lost so many things, so it was a difficult time to live. Still, my father and his friend helped each other and started all sorts of businesses together. I was young but I could see how wonderful the friendship was between the two men, and it has left a strong impression in my mind to this day. One thought behind starting the preservation efforts was that if they were alive, they would have wanted the house to remain.

When I began thinking about the how to utilize the Former Ouchi Residence, I considered the wishes of the ancestors, and it was my hope that it would become a place that could contribute to local residents’ cultural projects. It never crossed my mind to turn it into a restaurant.

My colleagues and I in the preservation society were all housewives, so we decided that we just would do what we were able to do. We began to manage the house by hosting events such as concerts once every two months or so, for visitors to enjoy their experience here. The problem was, however, that there is not a single restaurant or store in this secluded area. As it so happens, I like to cook, so when lunchtime came around, I started to make meals for the guests with whatever was on hand, such as somen (thin wheat noodles) and chahan (stir-fried rice).

As time went on, visitors began to bring their parents and friends to eat the food, and things started to get out of hand.

We then decided in the Preservation Society that we would serve meals for about half of the week and raise funds to enhance the place. This is how we began to operate the restaurant.

My mother grew up in Gyeongseong (present-day Seoul, South Korea). She was of small stature, but she was broad-minded and kind. My father was a strict person. Both were very good at putting things into words, and even when it came to cooking, they taught by explaining things in exact terms instead of showing how it should be done.

My mother got seriously ill just before the war ended, and we were told that she would not have much longer to live. I was about to enter the first grade of elementary school around the time, but it became my responsibility to cook for my family. I didn’t know how to cook yet, so I absorbed everything that my father taught me.

Today, everywhere you go, you can find rustic-style dishes and vegetable cuisine. To entice city folk to come all the way here, I think that we need to offer things that are even more appealing than what is available where they live.

I was very conscious about creating pleasurable meals that were made from rural ingredients and still had surprising elements. I think I also pushed myself because I was looking forward to hearing the guests’ exclamations of delight.

I believe that 1+1 equals 3 in my world of cooking. The “+1” in that equation is the affection I feel for the food and the people who eat it, and that was important to me (as it made everything more than the sum of its parts). I really poured my affection for the visitors into the cooking, dishware, chopsticks, and chopstick holders on each tray.

Ultimately, I just like people. That’s why it was always fulfilling to want the guests to enjoy the meals and their time here.

I am from the generation that doesn’t find pleasure in consumption. It’s more enjoyable for me to come up with my own ways of living each day. It’s more fun to go into the mountains to find ingredients there when I don’t have something readily available at home.

I’ve always been self-sufficient in this way, and I’ve always felt incredibly abundant and happy. If I could live my life all over again, I think I would lead the same kind of life as I do now. It’s just so much more pleasurable to create than to consume things.

I suppose it’s good to purchase things every now and then, but when you become absorbed by consumption, you just keep buying and buying and still aren’t satisfied, and you find that there is no end.

I think that it’s the same with cooking. I feel that it’s far more gratifying to use local vegetables and come up with different ways to prepare them into delicious, beautiful dishes than ordering ingredients from far away.

When no one lives in a house, it’s as though it were dead. This house was exactly like that before we began utilizing it for our projects. That is why I wanted to turn it, as much as possible, into a place where people would gather. All I thought about was for this house to become a kind of ancestral home that is warm and welcoming for everyone, where people living in the city would arrive and feel as though they had come home to an unchanged, traditional landscape of Japan.

In this sense, as diverse individuals came together and accomplished many kinds of projects, I feel that we were able to build relationships of mutual understanding with our visitors. We always felt so enriched by the support we had from people from all over the country who considered this place to be their home in their hearts, so much that not only me but my colleagues also say that working at the Ouchi Residence was the most enjoyable time of our lives.

What makes me so happy now is that the local government and the people involved with this house have begun to discuss and think together about the management of this place.

The authorities were not involved at all at the beginning, so after all this time, remembering how things were when we first started, it’s almost like a dream that they are now thinking about the future and trying to nurture successors.

Many people attended the anniversary celebration a few years after the renovation, and they stayed overnight in the house as well. I went out to take a look that evening and saw how the entire house was lit up and filled with people, and it appeared to be so cozy. Someone said to me, “Maki, this is what you had hoped for all this time, isn’t it?” It made me so happy, having this person realize how I’d felt and seeing what the house had become, and I stood there gazing at it for a long while. Everyone was really enjoying themselves.

Time flows too fast now, doesn’t it? Until my generation, changes were slow and things moved at a more comfortable pace, which is why I think culture had continued to be inherited.

We don’t know how the times will change again from now. We don’t know if it’s going to be peaceful, and we may even face an era of food shortages (here in Japan again). I am confident that I would be able to continue leading an abundant life even under such circumstances.

The lack of material goods does not mean lack of wealth, because there are so many things that can be enjoyed in that absence. (End)

Maki Tanaka is a Yame City native who launched the preservation efforts of the Former Ouchi Residence, with which she has a personal association that goes back to her childhood. As a member of the Preservation Society of the Former Ouchi Residence, she undertook conservation and utilization of the house for many years after it was restored. The Society’s elaborate, homemade cuisine “Haha no Zen (Mother’s Meal)”and other efforts to continue the lifestyle and culture of the region became widely known, and to this day, they enjoy heartfelt relationships with visitors who came from all over Japan.

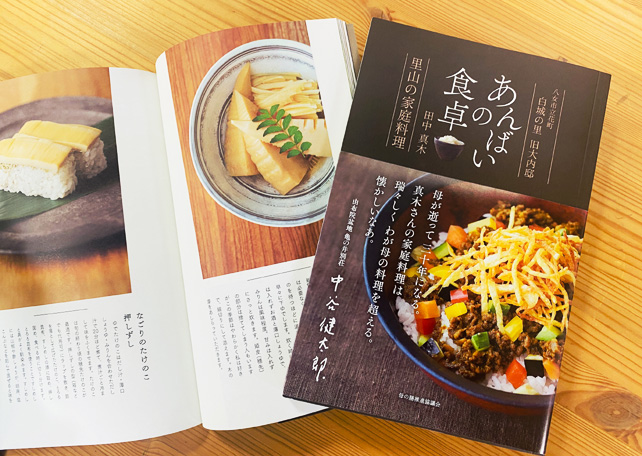

Roughly translated into English as “Dishes Made with the Art of Seasoning,” this is a valuable booklet written in Maki Tanaka’s words alongside beautiful photographs that share her world of cooking, in which she interacts with her ingredients as she prepares each dish.

It is the birthplace of Chozo Ouchi, who became a member of the Japanese parliament during the Meiji Era (early 20th century) and worked to help pass the General Election Law, which extended suffrage to all males aged 25 and over, and to improve Japan’s ties with China.